The critical error behind almost all reasoning about “racial profiling” for terrorists

Posted: February 18, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: 9/11, Ann Coulter, ethnic profiling, Islamophobia, racial profiling, racism, religious profiling, Sikhs are not Muslims, stormfront dicks, TSA 1 CommentProponents of racial (ethnic, religious) profiling for terrorists inevitably begin by citing the same demographic comparison. In the words of notorious racist Ann Coulter,

“The perpetrators [of terrorist attacks on Americans since 9/11] have all had the same eye color, hair color, skin color and half of them have been named Muhammad…This is not racial profiling; it’s a description of the suspect.”

Cheekiness aside, the argument is simple: A terrorist is more likely to come from x-racial-ethnic-religious group rather than groups y or z; therefore, we are warranted in searching for terrorists among persons who are (or appear to be) from that group particularly. This might entail singling out men fitting this description for baggage or ID checks in subways, or funneling them through a separate check-in line at airports.

For the sake of argument, let us assume that Coulter’s data on terrorists is correct—that most terrorists come from this Arab/Muslim sector (though in fact they don’t). Let us also assume there are no logistical or moral obstacles to profiling (also dubious).

My objection, rather, concerns the form of the argument. In short, Coulter’s numbers could be 100% sound, and it still wouldn’t make racial profiling an effective technique for finding terrorists.

* * *

The problem is the profiling argument gives way too much weight to the (statistical) relationship of ethnic groups to one another—that is, to the percentage of terrorists within one group as compared to the percentage in each of the others. I contend this relation—the very lynchpin of the profiling argument—has precisely zero relevance to the business of hunting terrorists. If we’re thinking properly, what should matter instead is the statistical relationship of terrorists to their own racial groups.

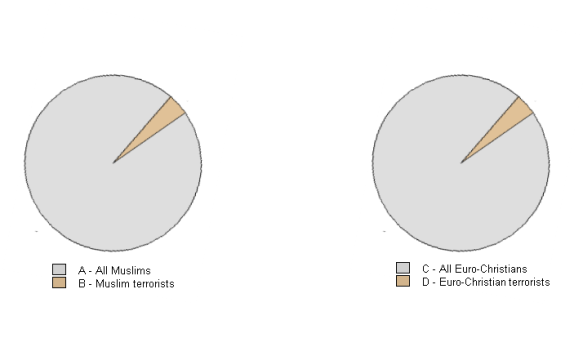

To put this visually (proportions not accurate):

The ‘profilers’ only care about how the beige sliver on the left compares in size to the sliver on the right: If the right is bigger, they say, we should search A for terrorists, rather than C. But this comparison is irrelevant. What matters is not which sliver is larger but how large—in absolute terms—the larger slice actually is.

Put another way, the most this kind of comparison by itself could tell us is that terrorists are unevenly distributed among ethnic groups. What it cannot tell is whether terrorists are represented in any one ethnic group highly enough to make profiling a viable technique for finding them. Just as only knowing your meal is bigger than your neighbor’s will not tell you whether it is big enough to satisfy you. (For both meals could still be very small.)

Testing profiler logic: Two analogies

Some everyday examples of similar reasoning should further clarify.

Analogy #1: Children from “broken homes” are by some percentage more likely to become serial killers later in life than children from two-parent homes. This hardly means that shaking down a bunch of people with divorced parents would be a wise deployment of police resources. Even if 100% of serial killers had divorced parents, those products of divorce who actually commit serial murder are such a tiny minority among all children of divorce that the strategy would still be suspect.

Clearly, the key statistic isn’t (i) how many offenders come from divorce, but (ii) how many people who come from divorce actually turn out to be offenders. Focusing on the first stat only tells us that one set of odds is greater than some other set of odds; it tells us nothing about how good the second set of odds—the one we are banking on—actually is. We may as well say that buying two Powerball tickets has a greater chance of winning millions than buying just one; that’s true, but it doesn’t make buying one or buying two very likely to yield a winner. Likelier is still miles away from likely.

* * *

Analogy #2: Imagine we have a haystack which has some probability of containing a needle. (Let’s say, there is some probability that one of the straws is a needle.) Let this equal the probability that a given, random person fitting the “terrorist profile” is a terrorist; that is, drawing a random straw is as likely to yield a needle as detaining a random “Muslim” is likely to yield a terrorist. Let us assume this method of finding needles is ineffective, counterproductive, even (somehow) immoral; also, that we have some far better method of finding needles in haystacks—using magnets, X-ray, floating the straw on water so the needle sinks, etc. We still want to root out needles, but have long abandoned the strategy of drawing random straws.

Now, imagine we discover that all along there has been a second haystack nearby which has an even lower probability of yielding a needle than our haystack. Perhaps we discover several more, each with some probability of success lower than the original, but still greater than zero.

It has become clear that a needle is more likely to come from the first haystack than from any of the others. Still, it would be irrational in the highest to conclude that we should, on this basis, resume our random straw-draws. The simple fact that a less promising haystack exists does not magically make checking this stack a good idea, if it wasn’t a good idea before. If an activity’s probability of success is extremely low, it isn’t made better just because there exist other activities whose probability of success is even lower. (That’d be crazy, right?)

Conclusion

Profiling advocates are confusing better odds with decent odds. The simple fact that terrorists are more likely to come from Arab/Muslim men than from some other group doesn’t mean that the likelihood of randomly finding terrorists among Arab/Muslim men is very good at all. And that is the real question.

So: Just how good is that that likelihood? I haven’t exactly crunched the numbers; you can do the math if you like. (The burden of proof is on the profilers anyhow.) But there are millions of persons in the world who fit Coulter’s “profile,” and the number of these who commit terrorist acts against Americans is, in relative terms, very nearly zero. Even fewer do so in those stereotypical ways that profiling would address. Fewer yet operate in the U.S., where ours laws can actually penetrate.

Clearly, we are dealing with numbers akin to those “children of divorce” who commit serial killing. It is quite likely that if we incarcerated every other Muslim male in the world, it would register nothing in practical terms to diminish the odds of the next terror attack. Yes, we can theoretically halve a .000003% chance of something. Getting married later in life will halve one’s chances of committing suicide someday. Hell, there is shit you could do right now to seriously diminish your chances of being brainwashed by a cult or eaten by a mountain lion. I mean, Who gives a shit? Differences of this infinitesimal grade do not drive anybody’s consideration of anything in the real world; far less should they drive national security policy.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

Bonus: The above aside, profiling is still a shitty idea

This is not to mention that radical Islamists come in all “colors” and (duh) will easily work around any profile we make.

In addition, ethnic profiling is counterproductive; it alienates the very communities which are most critical for intelligence on (and testimony against) the potential attackers that move and live among and gain cover from them. As social psychologist Tom R. Tyler masterfully argues in his seminal Why People Obey the Law, individuals who feel they are singled out unfairly by law enforcement tend to avoid contact with the latter as much as possible; at the same time, they internalize this treatment, minimizing their stake in the system, giving them less incentive not to offend.

Finally, as with finding needles in haystacks, we have alternative strategies for fighting terrorism that are superior to profiling. Granted, jihadists will cite a number of gripes against the US if you ask them. Some of these concern cultural factors like women’s liberation and sexy music and movies. But according to the evidence, these aren’t the “root” reasons they turn to terror. As I’ve argued elsewhere, the violence is above all a response to US foreign policy in and toward Muslim countries and populations. Bin Laden, for instance, clarified his grievances across many years in interviews with Robert Fisk.

Michael Scheuer’s Imperial Hubris: Why the West is Losing the War on Terror summarizes nicely the main Islamist concerns; to paraphrase:

- U.S. support for Israel’s occupation of Muslim Palestine

- U.S. and other Western troops in every state of the Arabian peninsula

- U.S. support for Russia, India, China, Phillipines and Uzbekistan against their Muslim populations and militants

- U.S. pressure on Arab energy producers to keep oil prices low

- U.S. military and economic sanctions on Muslim nations (sometimes through the U.N.): Syria, Libya, Iraq, Sudan, Pakistan, Iran, Indonesia, Somalia

- U.S. support for apostate, corrupt, and despotic Muslim governments (often a vehicle for the above concerns)

- And now, via the WOT: U.S. occupation of Iraq and Afghanistan; incarceration without trial of thousands of Muslims suspected of being mujahideen; pressure on Muslim governments to track, control and limit Muslim’s donations to charitable organizations; pressure on these governments to tailor school curricula to give a more pro-Western brand of Islam

Thankfully for us, these concerns are quite reasonable, technically solvable, and are morally “overdetermined”—that is, they should be met for a host of reasons even aside from fighting terror.

Debunking “Che Guevara, racist” again

Posted: February 8, 2014 Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: apartheid, Cuba, Humberto Fontova, Nelson Mandela, South Africa, stormfront dicks Leave a commentA tertiary effect of Mandela’s death has been the reactivation of right-wing criticisms of Che Guevara, the Argentine-Cuban revolutionary hero. In an effort to slur both, the South African leader has been liberally quoted praising the latter. Critics have drawn their own seedy parallels between the two legacies, some dubbing Mandela “the Che Guevara of Africa.”

The “Che as mass-murderer” trope has long been an anti-communist staple. Only more recently are critics eager to establish that Che was also an anti-black racist. From what I can tell, this conceit is directly traceable to the “scholarship” of Humberto Fontova, a Cuban expat numbskull whose sources are almost entirely reducible to (a) Che’s travel diaries, predating his revolutionary turn, and (b) “shit some Cuban person told me.”

The evidence for Che’s racism is a single sentence from those diaries—one which, by the way, Fontova typically misquotes. As recounted (correctly) by Che’s biographer:

“The black is indolent and fanciful, he spends his money on frivolity and drink; the European comes from a tradition of working and saving which follows him to this corner of American and drives him to get a head, even independently, of his own individual aspirations.”

So. What to make of this?

In context, this is a young man’s single, private impression on seeing black people for the first time. Note that these are particular black persons; there is no evidence Che would extrapolate from his localized experience in a Caracas slum to “the black race” in a general sense. As a diary entry, it was a thought which happened to be written down, unfiltered, unedited, unintended for publication. While chauvinistic, naive and snooty in a vein typical of the writer’s upper-class Argentine background, the quote is not particularly nasty. (As with Barbara Bush’s observation that the Superdome was a nice vacation for the Katrina refugees, it isn’t clear the speaker has bad feelings toward his subject.) It was written—for fuck’s sake—in 1952, two years prior to Brown vs. Board of Education formally ended segregation in the US.

Most importantly, to repeat, the quote is all we ever get. From this alone Fontova and his appropriators deduce Che’s racism. They thereby summarize the man as “a racist”—not “an ex-racist,” not “a man capable of bad ideas about race.”

Is that enough, though? Is the quote (is any quote?) so bad that there is absolutely nothing the speaker might have conceivably gone on to think or say or do in his remaining years which might have atoned for or mitigated it? Is there nothing else that matters—that could matter?

We can debate the severity of the statement. The important point is that, whatever it means, Che changed his fucking mind. We know that he went on to condemn racism explicitly, privately and publicly, and in terms far less ambiguous than the above “affirmation.” He went on to lead one of the most effectively “unracist” lives in history:

In his 1964 address to the UN, Che railed against color segregation in the American south, which persisted despite the recent passage of the Voting Rights Act. Arguing the federal government hadn’t done enough to restrain the KKK:

“Those who kill their own children and discriminate daily against them because of the color of their skin, those who let the murderers of blacks remain free—protecting them, and furthermore punishing the black population because they demand their legitimate rights as free men…How can those who do this consider themselves guardians of freedom?… The time will come when this assembly will acquire greater maturity and demand of the United States government guarantees for the life of the Blacks and Latin Americans who live in that country, most of them U.S. citizens by origin or adoption.”

In the same speech, Che called slain Congolese president Patrice Lumumba a “hero” for resisting the white Belgian colonists; lauded the black singer Paul Robeson, who brought the Negro Spiritual into American pop culture and who was persecuted by American intelligence for socialist ties; and condemned South African apartheid when nobody in the West was yet talking about that issue.

Following the military success of the Cuban revolution, Che aided the African independence struggle in the Congo. He led an all-black contingent of a dozen Cuban soldiers and native Congolese against the colonial forces, requiring him to shoot at white South African mercenaries. Later, Che met with leaders of Mozambique’s independence struggle, offering similar help to the black FRELIMO army (which was declined). (Of course, as Cuba’s own population is largely black, Che’s assistance to that revolution falls in the same category as the above.)

Che also led the integration of Cuban schools, beaches and other facilities years before the island’s American neighbor. Finally, at risk of playing the “some of my best friends are black” card, Che’s most constant companion during the revolution (and consequently his personal bodyguard) was Harry “Pombo” Villegas, who was, like almost all the men in the units Che led, a black Afro-Cuban. Pombo is still living and has in his memoirs attested to Che’s anti-racist credentials. (In this assessment, he joins black leaders like Malcolm X, Nelson Mandela, and Stokely Carmichael.)

* * *

The charges of racism are laughable enough. But equally so, the straining uses to which this fantasy is put. The slander is clearly an effort to discredit not just the man but his entire legacy and those global efforts which continue to draw inspiration from it. This amounts to a clownish hyper-idealism by which the man’s inner feelings are lent the power to taint whatever he may have touched. Not only, as we have seen, is a diary blurb not “Che”; but neither is Che himself “the Cuban Revolution.” Whatever unsavory ideas Che might have carried around in his head, the Revolution effected real, tangible progress on race in an historical sense—no small thanks to Che’s own actions:

The greatest literacy bump in human history occurred after the Revolution. Illiteracy went from nearly a quarter of the population to less than four percent in under a year. This mostly affected rural Cubans of color.

The Revolution instituted an immediate 50 per cent reduction in rents and subsequently granted tenants full ownership of these houses. As a result, more blacks per capita own their homes in Cuba than in any country in the world.

Cuba’s revolution is well known internationally for its aggressively anti-racist foreign policy. Most impressive was Cuba’s role in the helping end the racist South African apartheid regime. From late 1975 to 1988, 300,000 Cuban internationalist volunteers participated in the war in Angola, routing the invading South African armed forces, thereby hammering a final nail in the coffin of apartheid. Angolan textbooks will forever teach this episode to elementary school children.

Finally, just as we cannot equate a youthful, renounced journal scribble with “Che,” neither can we equate Che, nor his Revolution, with “socialism.” It is certainly possible for either to have wronged and the socialist project remain theoretically viable. To this end, who gives a shit what Che thought, or even did? Those things are an interesting historical aside, but they don’t bear the load his critics want them to. Social science and activism isn’t religion; condemning the prophet has no power to indict the theory, or anyone else’s practice of the theory.

* * *

I will briefly address the other peg of the right-wing assault, the “Che killed a bunch of people” modality. In truth, nobody has sound figures on how many “loyalists” died in the Cuban Revolution—sure as hell not Fontova’s dumb ass. In any case, Che did run a prison for a brief time, and some people were tried and executed there. Unless these critics are against the death penalty in every conceivable case whatsoever, they must give us more here. They must critique the trials themselves, the evidence used and so forth.

Note also the death penalty was largely applied, and summarily so, as a humane preventative to the locals’ mobbing the prisoners—their former brutalizers—limb from limb. This is acknowledged by the most unsympathetic historians of the episode.

Justifiably or not, however, none of this business amounts to “Che killing people.”